Well, Jon and Kevin did a fantastic job of winning the 2021 90 Miler under very harsh conditions. They came in well ahead of the pack, in fact almost 60 minutes ahead of the other 2-man guideboat contestants.

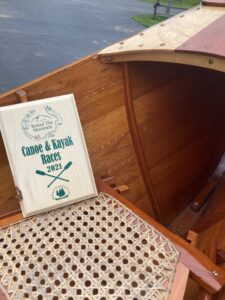

Some time after the race I received a package from Jon. I had no inkling of what it might be so I eagerly opened it. Here is what I found.

Jon took great care in acknowledging all who contributed to the great success that he and Kevin achieved. We know of the long hours he and Kevin spent practicing during the summer. They were meticulous in their preparation making sure that no detail was ignored. For example, you will remember that they had an extra set of oars ready if needed.

Jon and Kevin realized that their boat was integral to winning. They had great praise for Thankful during the race. But they took time to recall the origins of their winning craft; Caleb Chase, the designer of Thankful and me, her builder.

Let’s take time to recall the life of guideboat builder Caleb Chase. I chronicled his life in my book “Tale of an Historical Adirondack Guideboat and How to Build One“. Here is how the chapter on Caleb begins:

” Speaking of old times reminds me of old Caleb Chase of Newcomb, with whom I had a most interesting talk not long ago when I happened to be passing by his way. No Adirondacker of the old school but knows of the old boat builder of Newcomb, at least by reputation, for the famous “Chase boat ” has for over fifty years been regarded as the most perfect type of woodsman’s craft built or used in the North Woods. The staunch little products of the old man’s skill are found in every corner of the Adirondacks.” from Field and Stream, September, 1901. page 108.

So? Well, it was Mr. Chase who built the Queen Anne guidedboat. The Queen Anne was the guideboat whose lines I took to build Thankful. (The name given my third guideboat was taken from Caleb Chase’s wife, Thankful.) Caleb and Thankful settled in Rich Lake not far from Newcomb, NY. They had seven children and Caleb, through various endeavors such as boat building, gunsmithing and farming was able to provide his family with a comfortable life. The family compound grew to include an attractive home, a workshop, paint shop, black smith shop, a barn and an ice house.

At one time there were 70 guideboat builders in the Adirondacks. So what makes a boat built by Chase distinctive? First, Caleb was not hemmed in by traditional thinking. His name is associated with the then radical change in design of a guideboat’s stern. He realized that there were advantages to eliminating its traditional square-ended transom to make the boat double-ended. It made the boat lighter and easier to carry.

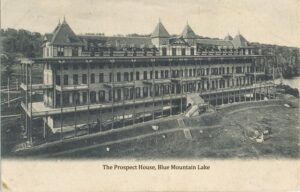

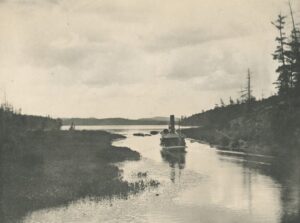

Caleb was quick to capitalize on the shift in guideboat requirements that occurred during the 1880’s and beyond. During that time guideboat design shifted from being primarily a workboat to a pleasure craft for use mainly by the well-to-do. These were either owners of or guests at the Great Camps or guests at the many hotels that sprung up in the region. Either venue, Great Camp or hotel, had guides who would take a gentleman as well as his lady friend out on a lake for a day of fishing, exploring or picnicking. Since the days of extended hunting and fishing trips were mostly gone, guideboats morphed into a “pleasure” vessel. Caleb identified several characteristics that would make the craft more appealing to this wealthier class of users. They were stability, durability, and beauty.

Guides would rate a boat as to whether it was “steady” (stable) or “cranky” (tippy). Cranky boats were judged to be poorly built. A joke went around that if you were rowing a cranky boat you should keep your hair parted in the middle. Otherwise, the boat would be more likely to capsize.

Chase made his boats more stable by making the beam wider and keeping the hull less inclined below the waterline.

Chase certainly knew that guideboat ribs were something of an Achilles heel. It is difficult to find root stock where the grain follows the shape of the rib over its entirety. At some point, particularly with ribs near the bow and stern, some ribs will exhibit cross grain. Cross grain is where the grain runs cross-wise rather than downward along the hull contour. This “cross grain” is where the rib is very weak. A sideways jolt, for example, from a careless boot could cause the rib to snap.

Chase realized that his customers would not be happy if their boats were plagued with an annoying number of cracked ribs. To counter this tendency, he made his ribs an 1/8″ thicker. The extra weight this incurred was no longer a consequence. By now guideboats had become a pleasure craft rather than a work boat used for week long trips for hunting and fishing.

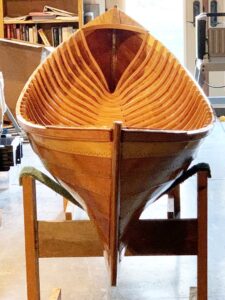

As far as beauty, Chase made some subtle changes to enhance the appearance of his boats. The decks of his boats are curved, rather than flat. There is a deck cap at the fore and aft ends that along with the upward sweep of the deck, brings a sense of motion to the vessel. The deck caps sport a brass feed-through used to hold a pennant or a jack light for hunting deer at night. His stems have a sense of boldness and confidence since they are quite larger than those of his competitors’ boats.

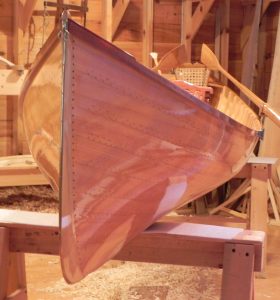

Bold bow stem of a Chase boat.

So how did I get involved in building Thankful. Have you ever undertaken something that, looking back, seems truly absurd? Well building a guideboat and writing a book about it seems that way to me now. But, in life, sometimes compulsions take over. Here I am finishing up my fourth guideboat.

For my part the beauty of a guideboat became an obsession. I really wanted to have a guideboat of my own. I don’t know where this urge to have a guideboat came from. I had never rowed one or even been a passenger in a guideboat. But I just had to have one. With four kids to raise I certainly couldn’t afford to purchase a guideboat.

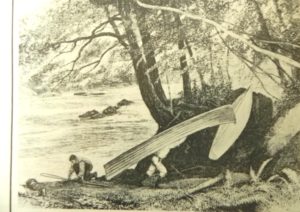

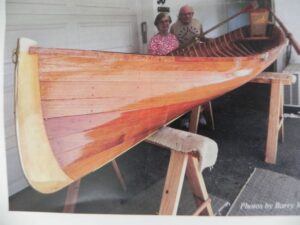

So the only way to possess such a treasure was to build my own. Fortunately I had some experience building small boats. My Uncle Donald started to build the Sairy Gamp, a very small canoe that has become a legend in the Adirondacks. When he lost interest in the project, I inherited the plans, materials and strongback necessary to build it. My son Stew and I built the Sairy Gamp, shown below.

I learned a lot building the Sairy Gamp. It would serve me well as I moved on to build a guideboat.

I began the project of building my own guideboat with nothing, no plans, or instructions. Fortunately, that would change. As luck would have it, there was a guideboat up on saw horses down the lane from our summer place. I asked its owner, Susan, if I could take the lines off her. She said “Sure, its yours to work with”. She said the boat was called Queen Anne and it was very special to her.

I later learned (and perhaps as I was working with Queen Anne) that guideboats have a rather simple DNA. There are a few vital measurements that are needed to build any guideboat. If you know the bottom board dimensions, and the stem and rib shapes you can build one. Something called the Boston Rule allows you to line off the planking. Nevertheless, I took every conceivable measurement off the Queen Anne. Much later, when I wrote a book on how to build a guideboat I was very happy that I had been so thorough.

I had two mentors, old time guideboat builders; who were tremendous in their advice and support for my guideboat building venture. They are Tom Bissell and Bunny Austin.

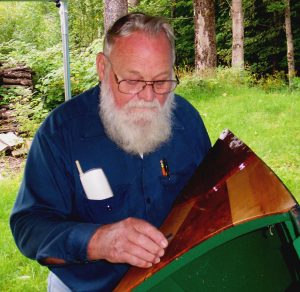

Above, Tom holds a perfectly to scale model of a guideboat that he had built. It is incredibly detailed, even down to tiny copper tacks along the plank seams.

Tom had taken a course in guideboat construction taught by Adirondack guideboat buiders and had built a boat using lessons learned from the course. When he learned I was thinking of building a guideboat, he offered to share his expertise with me. All of it was compiled in a scrap book that he shared with me one evening at his home in Endion.

Bunny Austin was another wonderful source of counsel.

Bunny’s family as boat builders goes way back. His great grandfather, Billy, started building boats at the north end of Long Lake in the late 1800’s. Bunny’s father, Merle, continued the trade as did Bunny. One of Bunny’s boats is in the Adirondack Museum’s collection.

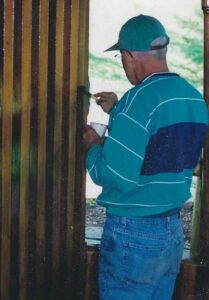

I began building my first guideboat in our home in Northern N. J, a quaint older home, built in 1918. My basement workshop was not plush, shall we say. Things in that department went from bad to worse when my family was forced to move when I lost my job. We ended up moving to New England and buying an old farmhouse in Sudbury, MA built in 1895. The basement shop had a dirt floor, there was no heat to counter the cold winds filtering through the cracks in fieldstone foundation, the ceilings were low and the lighting poor. But I persevered and finally my first guideboat, the Frances C., emerged.

So there you have it. Guideboat races are not won by only the grit and determination of the racers. The boat and those who designed and built it count too.