In part II of Where the guideboat came from? we will look into the contribution of William Austin of Long Lake. According to Stephen Sulavik we still have an artifact of one of his early guideboats. Before I get to that I need to give you some background.

Traveling southwest in the Adirondack Park just past Raquette Lake we come to Brandreth Park. The history of this oldest family enclave in the Park was recently documented in a book Brandreth, authored by Orlando Potter III and Donald Potter. It all started when Benjamin Brendreth immigrated to the New World in 1835 from London.

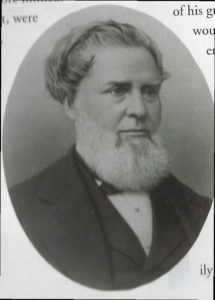

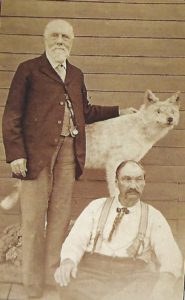

Benjamin Brandreth, from Brandreth, by O. B. Potter and D. B. Potter, page 1.

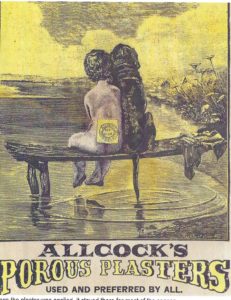

He brought with him to New York his grandfather’s formulas for Vegetable Universal Pills. Through a massive advertising effort and acquisition of Allcocks Porous Plasters, he soon outgrew his New York manufacturing capabilities and moved to Ossining, N. Y. (previously know as Sing Sing) By then he had grown extremely wealthy off his pill and plaster business as shown by his construction of a 30 room mansion with 10 bathrooms there.

He was asked to run and won election to the NY State Senate in 1849. There he became aware that entire Townships were for sale by New York State in the Adirondacks. These lands fell into the hands of the State as a result of their loss by England as a result of the Revolutionary War.

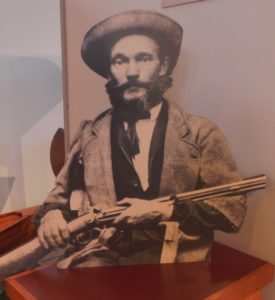

He sent his trusted employee, James Blandford to scout out these lands to determine their potential. Blandford, in turn, hired “Honest John” Plumley of Long Lake to guided him. Honest John appears later in Adirondack Murray’s book Adventures in the Wilderness. Honest John was highly respected as a guided and woodsman. Here they are together in a photo.

They are posing with the last wolf in the Adirondacks shot by Reuben Cary. Incidentally, wolves have returned to the Adirondacks (I have seen one). They are Coy-wolves, a hybrid of western coyotes and Canadian red wolves.

Blandford and Honest John scouted several townships being sold. They recommended that Township 39 be purchased. The purchase was recorded on March 21, 1851. Purchase price was $3605.70 or about 15 cents an acre.

The prominent body of water is Brandreth Lake.

I have known for some time that guideboats held a special place in the hearts of the Brandreth clan. I was told that only guideboats are allowed on the enclave waters (powerboats only in emergencies). The Potter brothers go on in Brandreth to say:

“It is with quiet pride that Brandreth owners extol their principal means of locomotion on all the water bodies of the Park: the Adirondack guideboat. This enduring aspect of our inheritance has its roots in the very first days of ownership, and persists over one hundred and fifty years later.” In the early days of the enclave so called freighter guideboats were used to haul the family’s possessions up the lake.

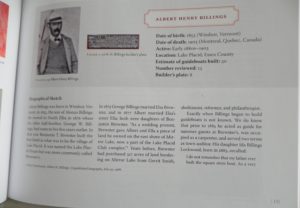

I was told that even today only guideboats are allowed on the enclave waters (power boats only in emergencies). As of the year 2008 there were 41 wooden guideboats in Brandreth Park. They represented craft built by many of the major guideboat builders of the 1800’s; John Blanchard, the Grant brothers, Reuben Cary, Wallace Emerson, and the Parson brothers.

The brothers also give a rather profound statement about the virtues of the Adirondack guideboat that reflects the love of the craft.

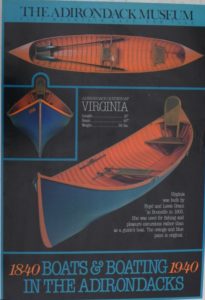

“The Adirondack guideboat is like a magnificent piece of furniture, painstakingly crafted by patient and skillful workers who spend months building a single boat. The keel bottom board is straight-grain pine, the thin ribs are spruce laboriously cut from the roots of a giant stump. The planking on the sides is white pine or white cedar, three inches wide and three sixteenths inch thick, each plank beveled at top and bottom, so as to overlap its neighbor to which it is fastened with copper tacks. Flathead wood screws hold the siding to the ribs, each of which is precisely beveled as to determine not only the beam of the boat but the shape of her sides. Viewed from above, the sides converge gracefully to the thin spruce stems at bow and stern.

When completed, the guideboat is a sleek double-ender, whose end-on profile, unlike the oval profile of a canoe, is more like that of a delicate teacup: from the narrow flat keel, sides rise straight up at the bow and stern. Before flaring out and continuing upward in a broad, gentle curve to the gunnels. The brass oarlock pins on the long oars, fit precisely into oarlock socket straps on the gunnels, making her very efficient to row from either the middle or bow seat, and some energetic crews have been known to row from both positions at the same time. Importantly, the caned seats, unlike those in a common rowboat, are set low so that the rower’s legs and knees do not interfere with the oar handles. The Adirondack guideboat is light in weight, tipping the scales between fifty and seventy pounds, and is readily carried by one person using a handcrafted wooden yoke.”

Brandreth Park holds an Adirondack treasure of inestimable value, the Book Case boat. I’ll talk about that next time.