In the last post we talked about how two boat builders immigrated to the Adirondacks from Vermont around 1850. They brought with them a wooden boat design that could be adapted to guiding. The style was known as a wherry. Wherries were quite popular in the colonies because they could assume many roles from hauling freight (coal) and passengers, to fishing for cod and salmon.

So why do I suspect that a wherry was the mom of the guideboat? Well, both have flat bottom boards, both were lapstrake or clinker planked, and both are the about the same length, 14-16 feet. And both used natural crooks, or roots for ribs, stems, and the transom. The beam of colonial wherries was wider than that of a guideboat. The reason for the guideboat’s narrower beam was that guideboats were carried over one’s head using a yoke. The boat was steadied by placing your hands on the yoke cleats on each side of the hull.

Here is the old Adirondack Museum’s logo showing how the guideboat was carried. (I wish they had kept the old logo. Everyone has mountains, but only the Adirondacks has guideboats).

Here I am demonstrating the optimum width of a guideboat as to how far apart my arms can comfortably spread to steady the boat while carrying it with a yoke. It is about a yard apart. The beam on the Chase boat I am reproducing is 38″.

John Gardner points out that wherries were built by “amateurs” or fellows who made their living doing other things than building boats, like farming and fishing.

In his book, Building Classic Small Craft, he describes how clever the “amateurs” were in putting together a wherry. It was done in someone’s barn or wherever there was shelter. No elaborate strong back for them. A couple of saw horses did just fine. The bottom board was gotten out and stem and transom fastened to it. The rocker was put in and this first stage was braced and shored. Next, a “shadow” or mold was placed amidships. Once everything was judged “plumb and level”, planking began starting with the garboard plank. Planks were bent around the shadow and allowed to take their natural curvature as they went around to the stem and transom. Since there was no talk of scarfing, the planking stock must have been long enough to go from stem to transom. These builders relied very much on their “eye” to ensure that the hull shape came out true. The planking stock, cedar, was lapped to butt tightly to its neighbor. Planks were bound together with copper rivets to render the seams water tight. This provided a very rugged hull that would last 50+ years of hard use.

The getting out of the transom is of special note. Gardner refers to Reuben Cary’s guideboat at the Adirondack Museum although not by name. Transom stock was carefully selected from cedar or spruce stumps, It required four roots all orthogonal (right angles) to one another. One opposing pair formed the transom itself. Of the remaining opposing pair, one formed the stern knee that attached it to the bottom board, and the other formed the curved stern post.

Here is the stern of Cary’s guideboat built sometime around 1870.

Gardner says ” these had to be hewed out of a single stump requiring much skillful and patient axe work.” He says as the specialized boat shops came on the scene in the nineteenth century they could not afford the time necessary to make such a handsome, functional and integral part of the boat.

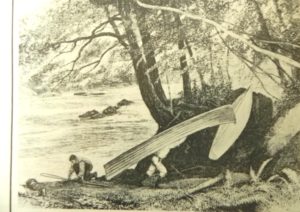

Here is another sketch of the early guideboats at the Raquette River Falls carry.

Next time we talk about boatbuilder William Austin and the “bookcase boat”.